Hello everyone! Without resorting to the already worn-out refrain of apologizing for the lengthy gap between updates, let’s just get to it, shall we?

First, take a quick peek at the brief animation/motion test video embedded below; for optimal results (and to best appreciate what I was testing), make sure the HD button is on, and click the ‘full-screen’ arrows icon in the lower right corner to view it as large as possible before hitting the ‘play’ button. Ready? Here we go:

I know, I know; it’s only about 12 seconds long (which is just the right length to be frustratingly not long enough), but I wanted to share a brief glimpse of what I’ve been working on, and offer the following explanation as to why this piece of the puzzle is so important:

This little clip represents the validation of a concept that began forming several years ago, while I was agonizing over how on earth to fund a fully computer-animated short film. Going through traditional channels had only yielded increasing despair as each response I received from investors/producers/distributors more clearly defined the conundrum I faced: computer animation costs a significant amount of money, and short films don’t tend to make any.

Even after the discovery of Kickstarter and the tantalizing potential of crowd-funding, I still couldn’t figure out how I could minimize the budget (back in “those days,” no Kickstarter project had come anywhere close to raising the amount I was considering). If you look at published production costs for recent animated feature-length films, you can begin to appreciate how large those numbers can get. Here’s a brief sampling of reported production budgets (in millions):

How To Train Your Dragon: $165

Wall-E: $180

Brave: $185

Toy Story 3: $200

Tangled: $260

Even one of the ‘bargain’ films like Hotel Transylvania at $85 million is fairly pricey to produce: running 91 minutes in length, that breaks-down to approximately $934,000.00 per finished minute. (Tangled clocks in at an even 100 min. which works out to a jaw-dropping $2.6 million-per-minute!!!)

Trying to sit through the end credits of these movies reveals one of the main reasons for the exorbitant costs — a never-ending parade of digital artisans that can easily number in the hundreds. (I can’t even begin to comprehend the technical and mechanical forces required to enable an army of people that size.)

Now apply those kinds of figures to my little production; even if I was able find a very small team that could manage to make it all work at $50K per minute, The Price (at just under 20 minutes in length) would still require a budget close to a million dollars! There was simply no feasible way to make it happen.

Until…

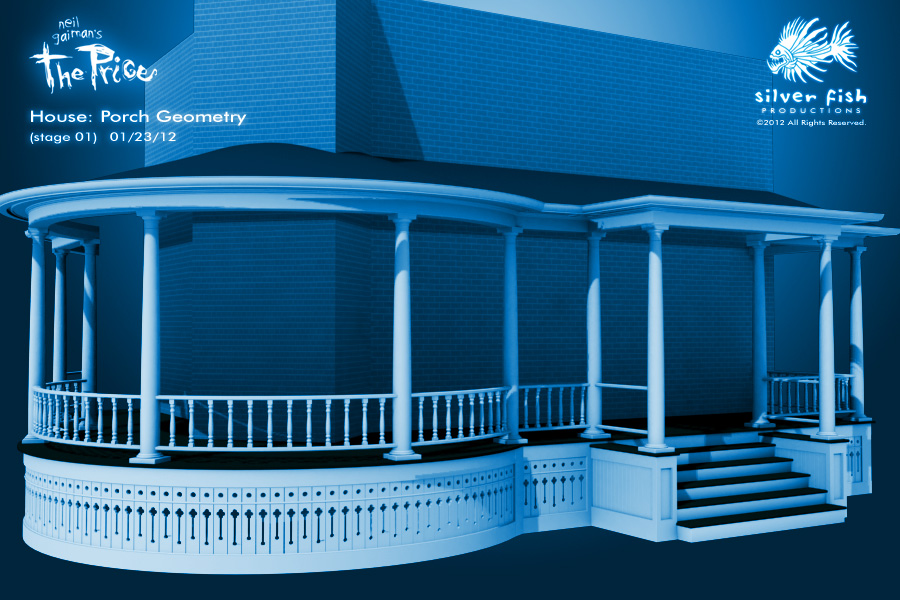

I started thinking about how effective the relatively crude animatic was at telling the story. Even though there were a few fully animated shots (featuring only a single character in a single environment), most of it was created with still images cross-fading into each other. I began to realize that I could try a similar approach with the final 3D models, and only render the parts of the image that were actually needed (rather than every frame, and every element within each frame). I figured with this kind of process, I could drastically reduce my projected budget — which I did — and even then, my Kickstater project was looking to raise (at that time) an unprecedented amount of money. (And all of you know the happy ending to that story!)

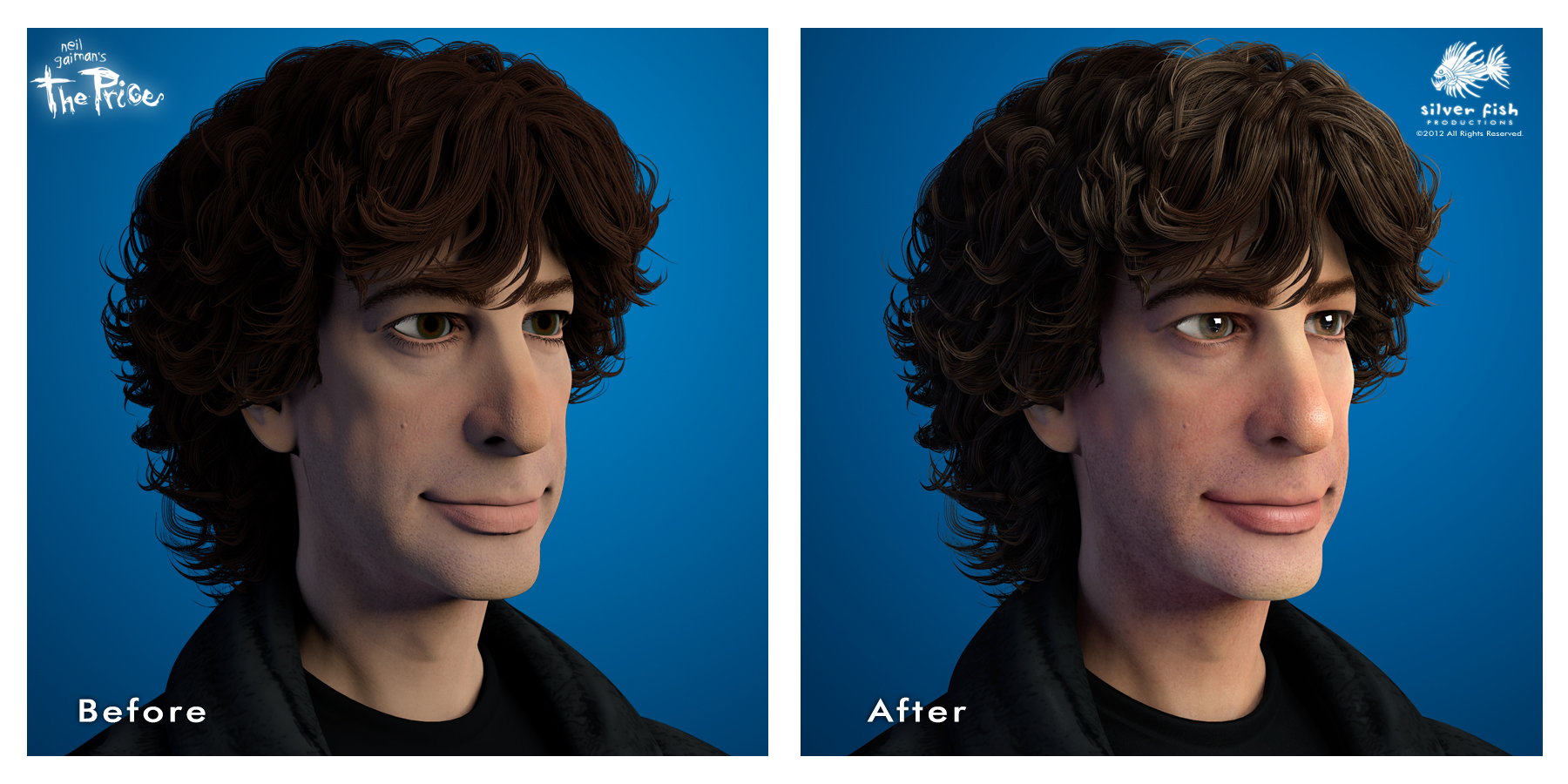

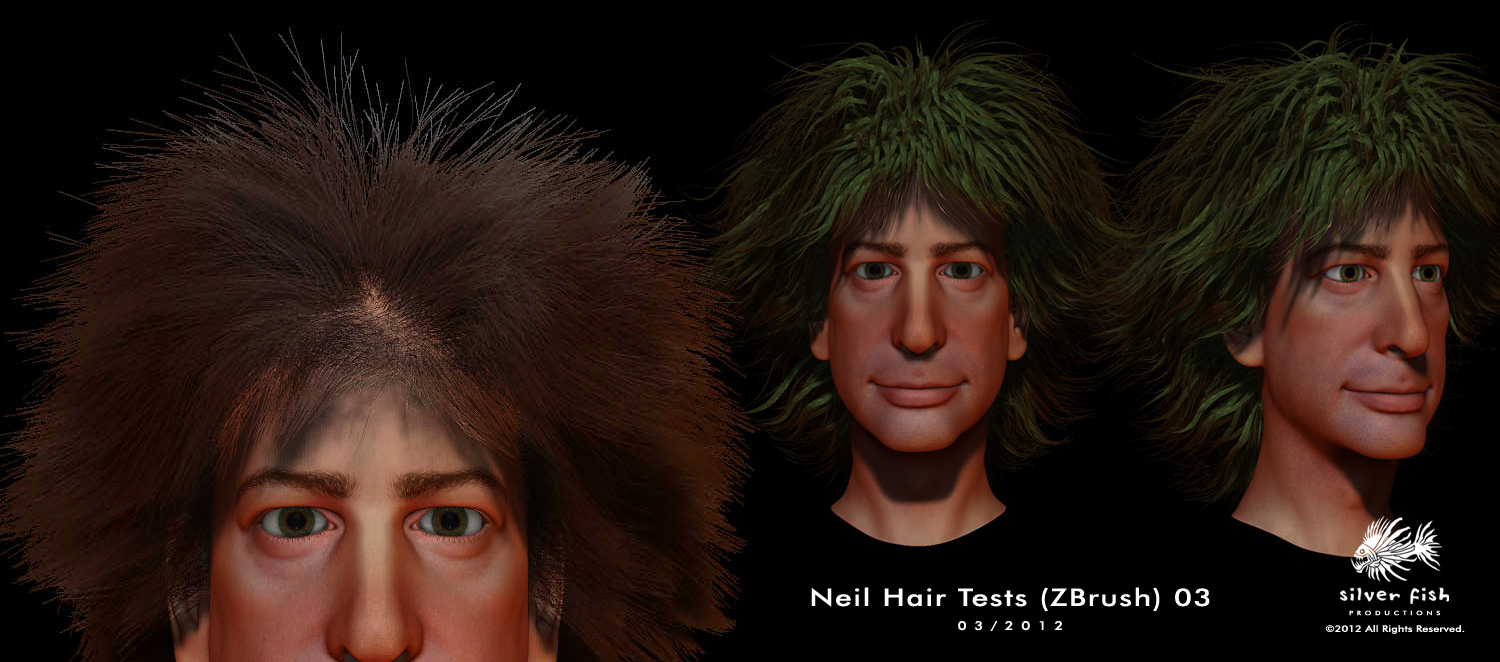

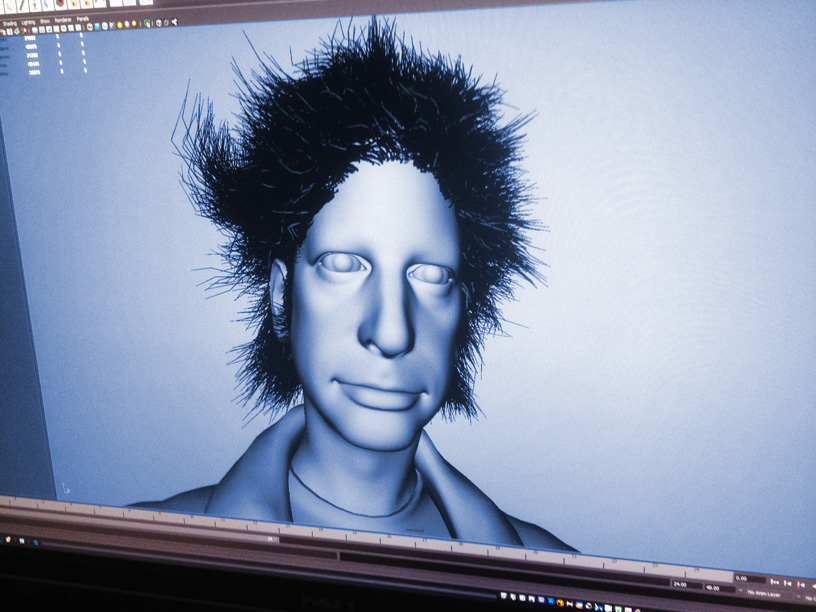

I began to develop methods and test techniques for realizing these ideas, and was greatly encouraged. Until I had my actual models, however, I wouldn’t know for sure — and that’s why I am so excited by this little, 12-second clip!

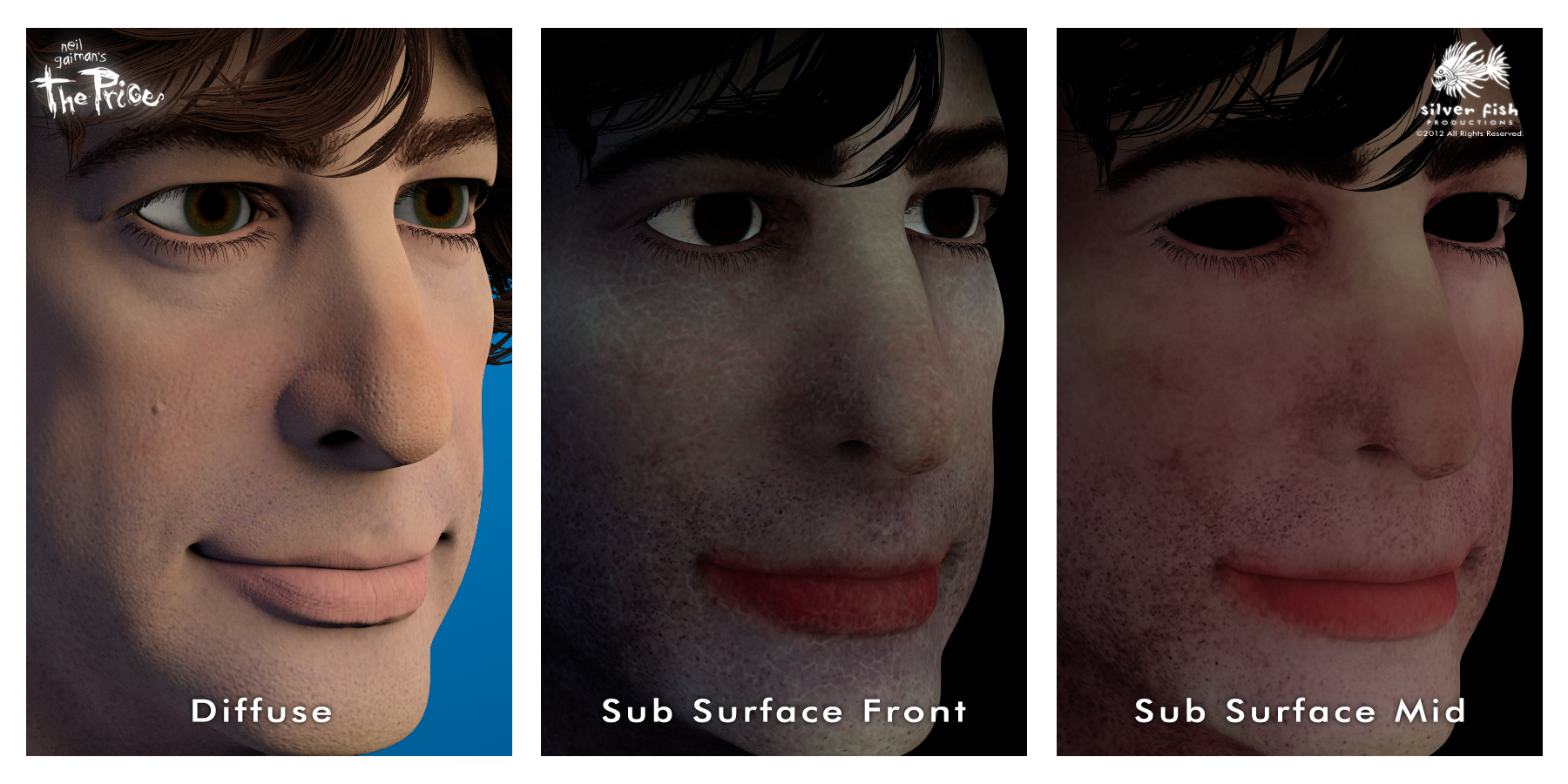

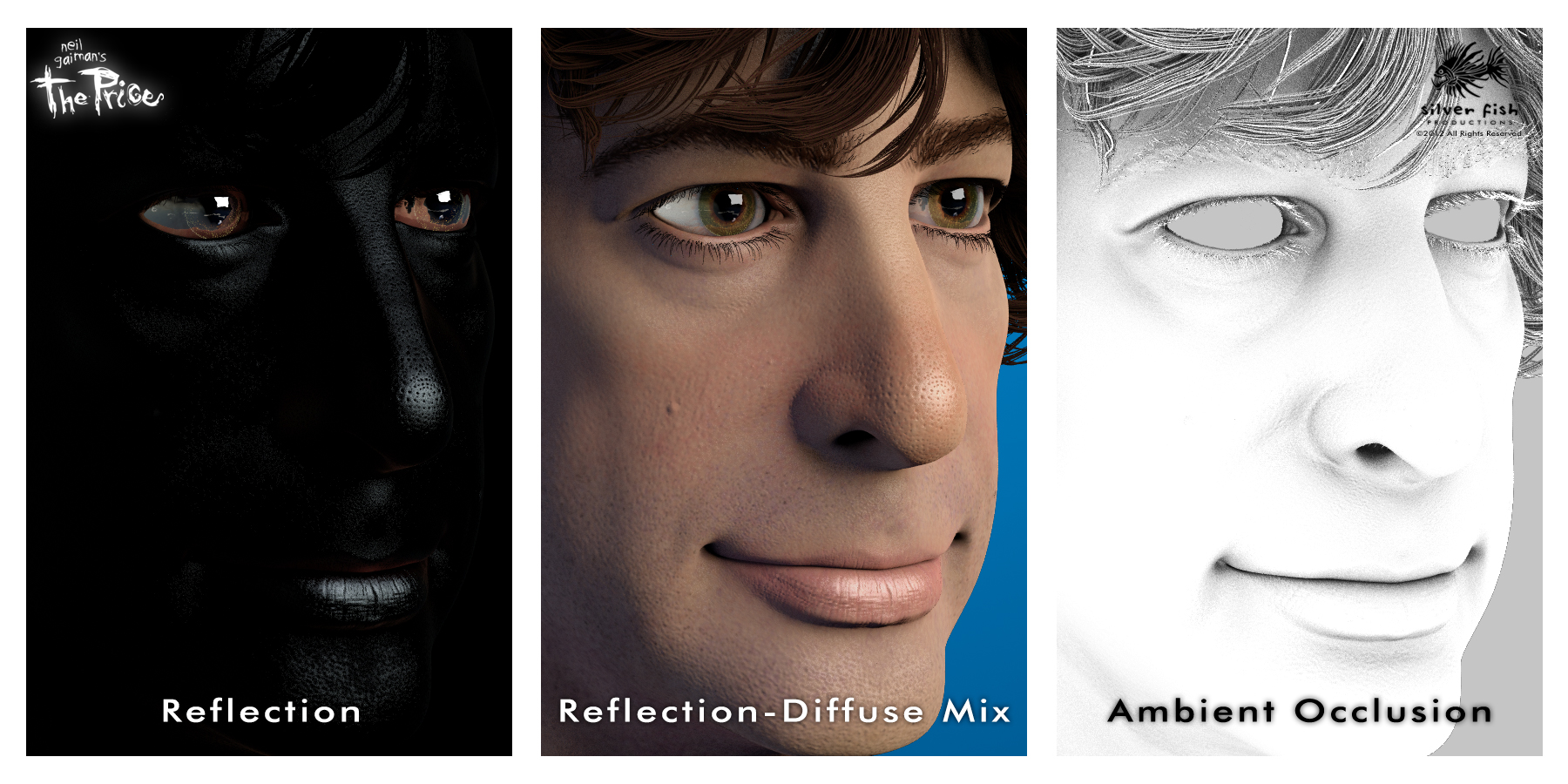

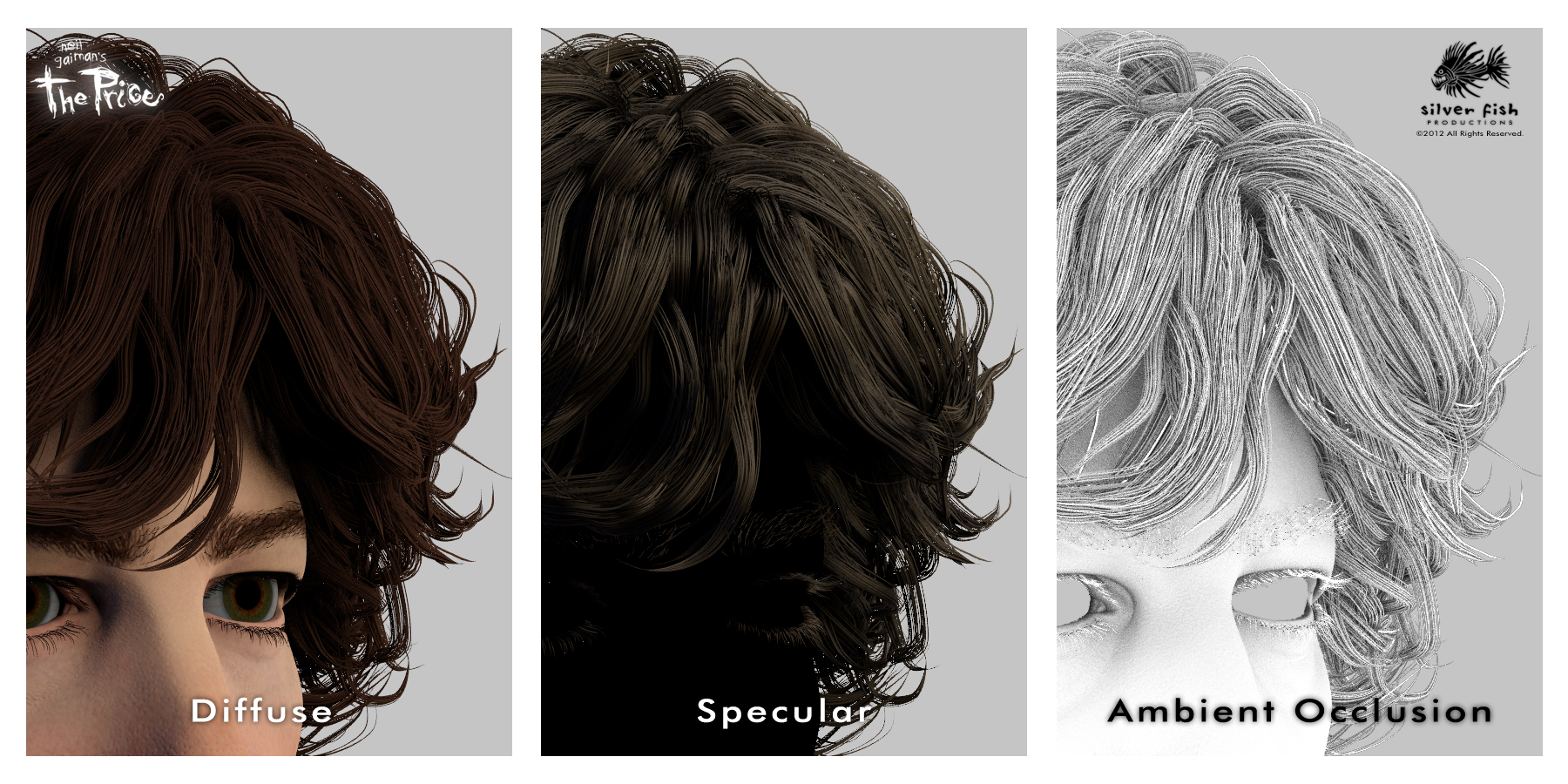

Instead of rendering all 288 frames, I rendered a single ‘hero’ image along with a few individual parts, like the eyes blinking or changing position, and the slight smile at the end. Even the background was created from a single still image, making the clouds appear to move across the sky with a little help from Adobe After Effects. Both Neil and the background were positioned in 3D space, and a virtual camera was created that pushed forward during the shot, changing angle and focal distance. If you watch closely, you can see motion in Neil’s throat as he swallows and even the nostril dilate slightly as he takes a breath (again, courtesy of the magic that is After Effects).

These details and others, like the suggestion of a breeze through the hair and adding some moving film grain to the final composite, all helped bring ‘life’ to what is essentially a still image. Even while adding music and sound effects, I was inspired to go back and add some birds flitting across the screen for a little extra movement.

And I think it all works really well! Consider these numbers: it took about 3 hours for my computer to render the two dozen elements needed to create this shot, as opposed to the hundreds of files that would have been required by going the standard route for all 288 frames (I shudder to think how long that would have taken).

There are many more advantages and developments that have sprung from doing the film in this way, but I hope this helps you understand more clearly what I’m attempting, and that you can see and feel the same level of excitement that I do in those 12, satisfying seconds.

Now, back to work!!!